As the owner of a website and a number of social media pages, I have had the pleasure of (virtually) meeting a lot of people. I enjoy talking with these folks, even if we don’t always agree. Polite discourse can be mentally stimulating and educational. Theories come and go. Ideas once considered to be rock-solid may be disproved. There are many things we will never know about early humans, but it’s always fun to speculate about those who tread this earth before us. It was during one of these recent conversations when a link to popular site was sent to me, by way of backing up his argument. If the page had been thoroughly researched and up-to-date (its sole citation was a paper from the 1860s), that would have been fine, but sadly, despite its popularity, it was a very poor source of information.

I have a systematic way to identify and assess research materials. I was fortunate to have held a managing editor position for an academic journal. It taught me about the academic publication process, which was quite a different experience as compared with the general media. This was a peer-reviewed journal that only published a small percentage of its submissions. Papers were carefully considered for their academic merit and whether or not the subject was current (or had an angle worth revisiting), but another important aspect was the references. How old were the papers that were cited? Were they published in a reputable source? You see, in the “publish or perish” academic world, a lot of papers are submitted to journals, leaving the staff to sift through for content that is both fresh and insightful.

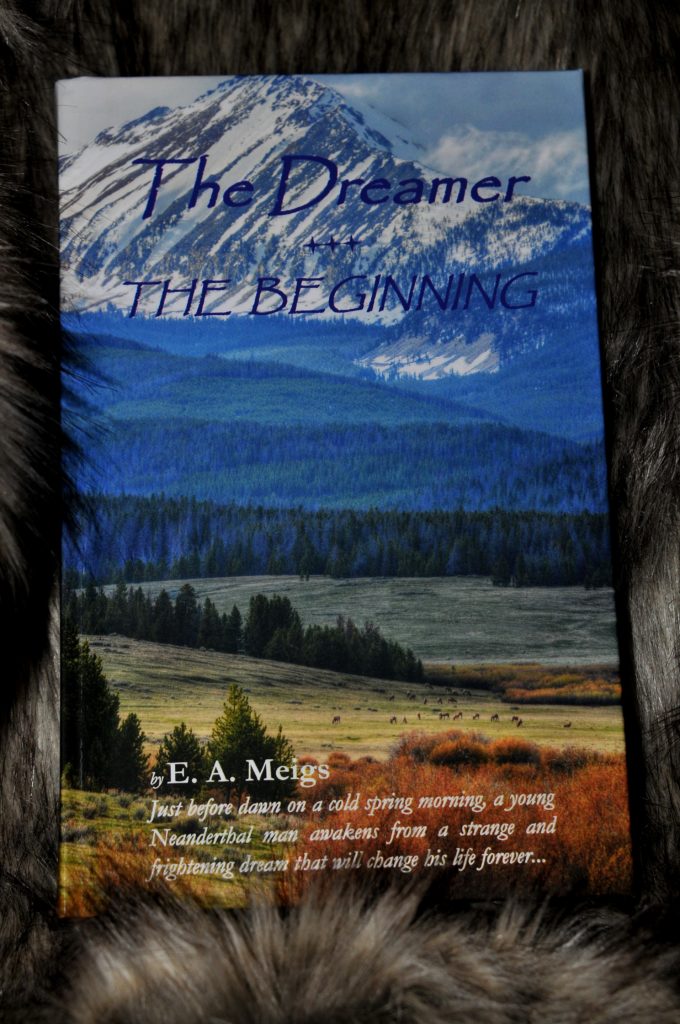

Nowadays I devote many hours to research for my books; over a thousand hours per year, in fact. I read everything I can find on the subjects of anthropology, osteoarchaeology, paleoanthropology, natural history, geology, ancient survival skills, and more. I assess my sources in the same way I assessed submissions. Is it current information? Are the references recent/credible? As mentioned in the video included on this blog, many of best resources are academic in nature. Not just published papers, but there are many wonderfully informative websites such as:

On the flip-side, there are also many popular websites – some associated with well-known entities – that may contain odd bits of misinformation. The field of paleoanthropology grows by leaps and bounds (especially during the last few years), so it requires a certain determination to stay on top of the constant influx of discoveries and new theories.

While one can forgive writers of fiction for using creative license as long as it is identified as fiction, it is unfortunate that entertainment articles are often put forth as serious science. You don’t have to be writing a paper or book to benefit from perusing the best resources, but I do think it’s important to consider the quality of the materials that will help you formulate your own ideas. Not that I mean to say you should shun any article that isn’t strictly scientific; there are many “fluff” pieces that contain good information, but you should go into it knowing it for what it is. If the article is entertaining and contains a few nuggets of real info, that’s great!

***

In the future I will be writing another blog about my non-academic research. After all, there are many facets of history that are not covered by science, alone. There is much to be known about primitive life that is best learned from those who practice those ancient skills!

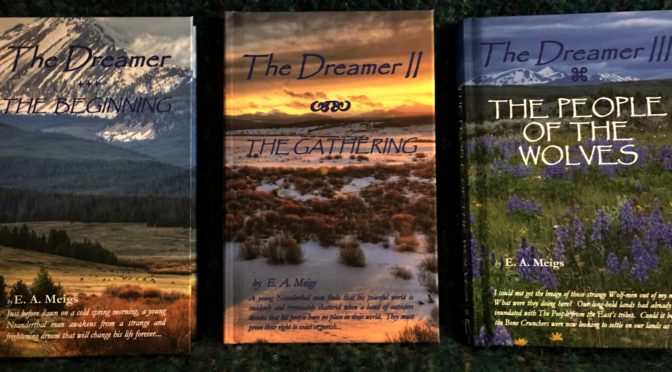

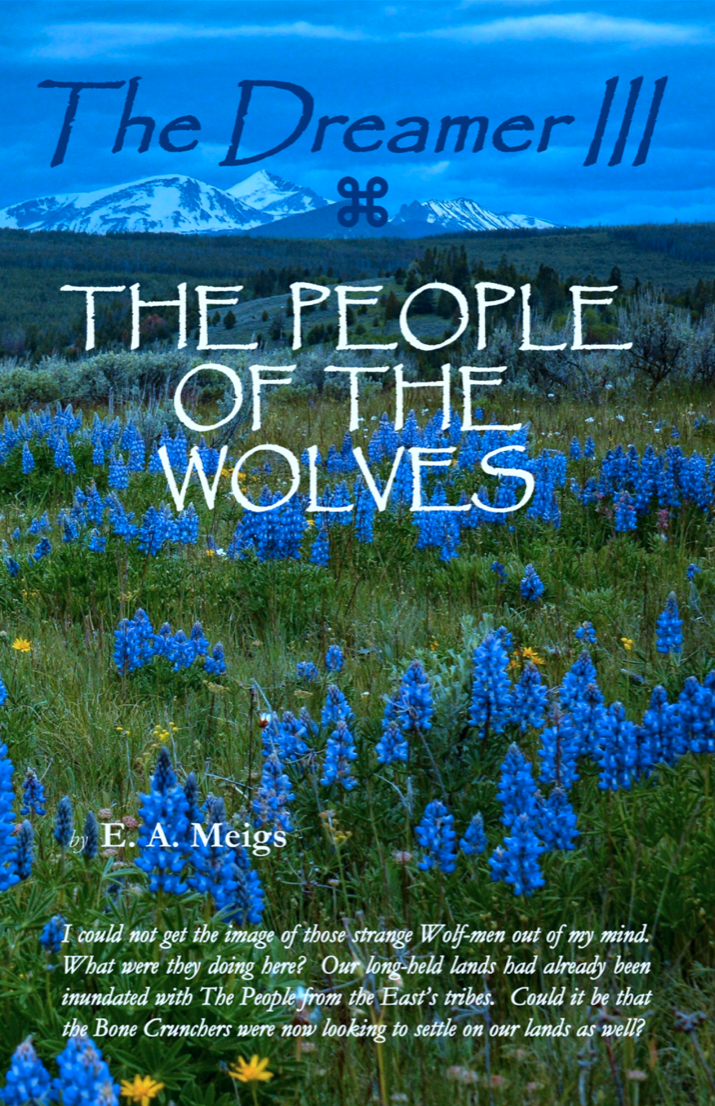

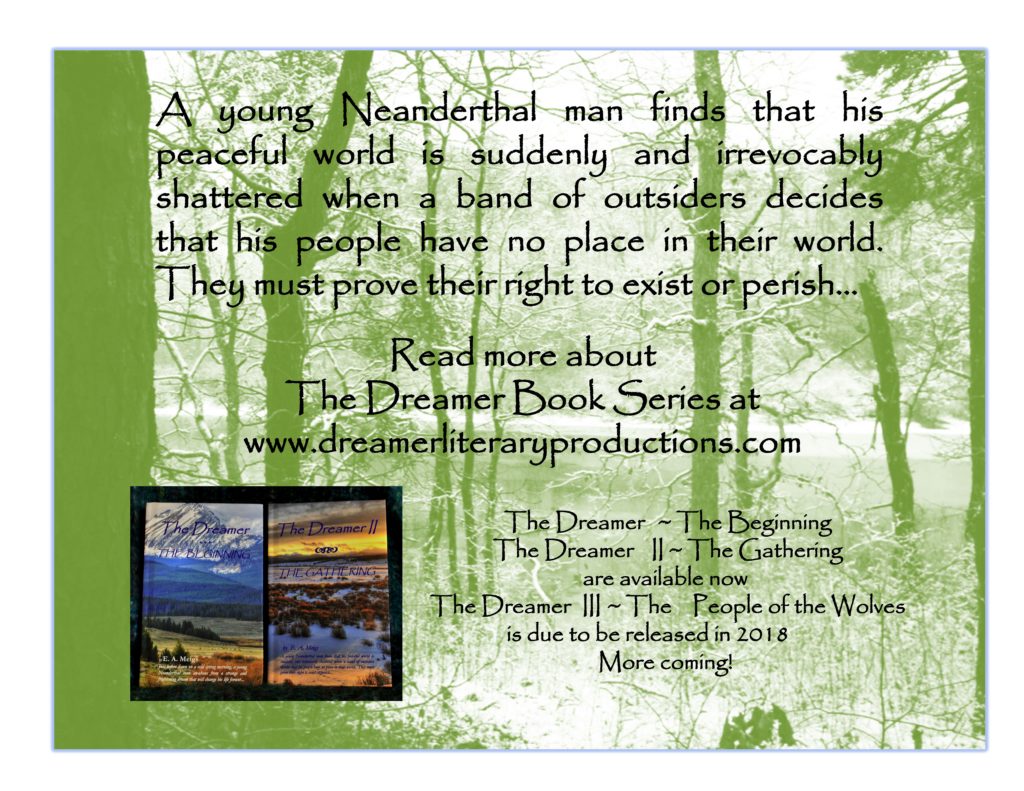

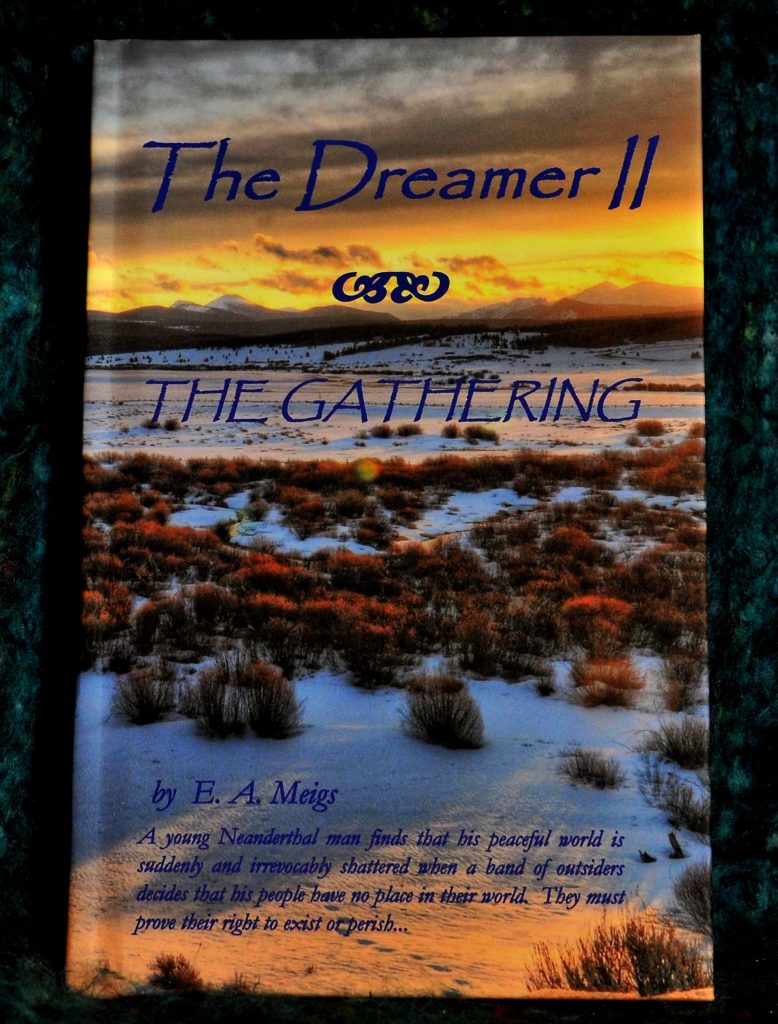

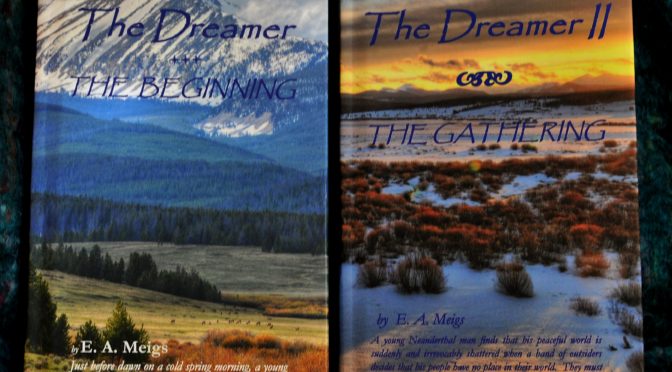

Header image: graphics by E. A. Meigs, cover photos by Paula Krugerud.